Concerto Crash Course

Solo concerto? Concerto Grosso? Here's a primer.

The concerto (pronounced con-CHAIR-toe) is a genre of classical music featuring a solo musician(s) playing with a full orchestra. Most of us can easily recognize a solo concerto when we see one, as they include only one soloist playing with an orchestra. The solo concerto became a favorite compositional style during the Baroque era and continues on into the modern era of music today.

A concerto grosso (Italian for “big concerto”) is a sub-genre of the solo concerto made popular during the latter half of the Baroque period (1600-1750). A concerto grosso is composed of several soloists playing with an orchestra. Generally speaking, concerti grossi are written in three movements, fast-slow-fast.

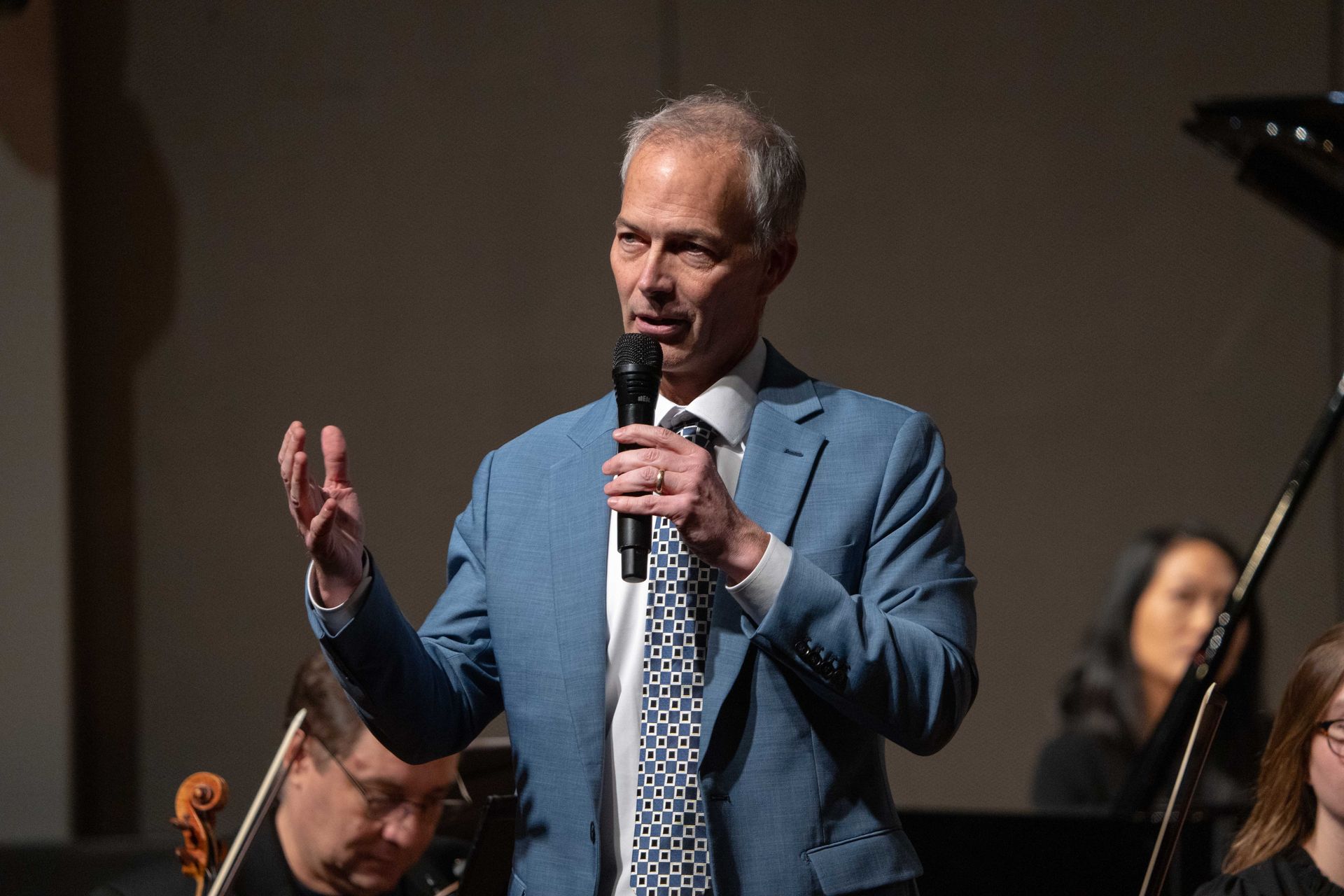

An example of a modern solo concerto: Percussionist She-E Wu performing Jennifer Higdon’s Concerto for Percussion with the Elmhurst Symphony Orchestra, Maestro Stephen Alltop conducting, on May 7, 2022. Photo by Elliot Mandel.

By the 1700’s the concerto grosso was in full swing. It had gained popularity in society, moving from the chapel (church music) to the court (social). Composer Georg Muffat (1653-1704) remarked:

These concertos, suited neither to the church (because of the ballet airs and airs of other sorts which they include) nor for dancing (because of other interwoven conceits, now slow and serious, now gay and nimble, and composed only for the express refreshment of the ear), may be performed most appropriately in connection with entertainments given by great princes and lords, for receptions of distinguished guests, and at state banquets, serenades, and assemblies of musical amateurs and virtuosi.

Musicians use specific terms to refer to different sections of a concerto gross:

- Tutti (pronounced TOO-tee) means “everyone” or the full group. In a concerto grosso, when the soloists and full orchestra play together, it is called a tutti section.

- Concertino (Italian for “little ensemble”) refers to the small group of soloists only.

- Ripieno (rip-e-AIN-o) translates to the “stuffing” or “padding”, and refers to the non-soloist musicians of the accompanying orchestra.

So, tutti is everyone, concertino is just the soloists, and ripieno is just the accompanying orchestra. Remembering these terms will help you make sense of statements like “the music moves back-and-forth between the concertino and ripieno before concluding with a grand tutti passage to bring the work to a climactic end.